Still Wild

Because we share our homes and lives with animals domesticated relatively recently (about 1500 years ago, as opposed to at least 15,000 years ago for dogs), we have the opportunity to live with and learn from beings who are much closer to their wild ancestors than are our other domesticated animals. This brings challenges—Igor’s chewed another hole in the wall!—as well as incredible benefits. For me, those benefits stem from the ways in which rabbits both retain so much of their wildness yet also accommodate themselves to our domesticated lives.

But we have to remember that while dogs were tamed to become partners to humans, rather than food, rabbits do not live to serve us or to please us. They are far more independent than dogs, which is one reason why we feel privileged when they choose to spend time with us, like watching TV or lounging on the bed. While there are some rabbits in my house I spend a great deal of time with, most have as much independence as possible. I want them to be free to be who they are, with as little external and human control as is practical. I believe that this comes down to four points: a realistic amount of freedom; an active social life; an interactive environment; and control over one’s life and environment.

A cage-free environment

Many of my rabbits once lived in small cages which did not allow for any natural movements or behaviors. With the exception of the disabled, the rabbits in my house now live cage-free. They have the room to run, play, climb, dig and modify their environment in ways that make sense to them. They have spaces to hide and private spots that they can call their own—at least until someone else claims it as their own. They spend their days chewing on cardboard, foraging for food, relaxing on their hammocks, and endless hours communing with each other—grooming, nuzzling, playing, “gossiping,” or just hanging out.

Social contact

Social contact between the rabbits, as well as with other species, allows many of their emotional needs to be met. My sanctuary rabbits live in a large warren in my house. The size of this group has ranged from thirty-five to sixty rabbits over the years, and right now is in the high thirties. Obviously, all of my rabbits are spayed and neutered, and, because of the many years in which this group has lived together, get along remarkably well. They don’t all like each other, but they’ve found their own friends and have created their own social groups within the larger group.

While these intraspecies relationships tend to mean that the rabbits will not bond with me (in fact, most will not even tolerate me touching them), it is much more important that they experience the richness of rabbit-to-rabbit relationships. This is especially true given the fact that these rabbits had all been abandoned, and many came from environments of either cruelty or neglect.

An interactive environment

Along with space, rabbits need toys to play with and structures to climb on, dig into and explore. This challenges the mind, exercises the body, and gives satisfaction. The inside of my house doesn’t offer a nature-like environment of grass or dirt. Floors are either tile or concrete; even the outdoor play space, our enclosed courtyard, is concrete. So they have cardboard, cloth and plastic tubes to run through; huge tubs of litter and hay to play in; and cardboard boxes of every shape and size to play with. They also have hammocks covered with synthetic sheepskin to lie on, and for the older rabbits who don’t do a lot of playing, this is their major hangout during the daytime.

Control

I try to put as much of the rabbits’ days into their own hands—or paws—as I can. While I do set morning and evening mealtimes, there is hay out all day that they can eat when they like. The sanctuary rabbits’ room has two doors: a human-sized door for me, and a rabbit-sized door for them that leads to the courtyard, to use whenever they wish. Although they are all inside at night, during the day they can go in and out regardless of the weather. A surprising number of them even enjoy playing in the snow.

No matter their background, most rabbits who end up in my home previously lacked control over any aspect of their lives. By providing an environment in which they may go to bed when they like, eat when they like, travel inside or outside when they like, interact with whomever they like, and modify parts of their physical surroundings as they like, they seem not only happier but more “rabbit-like.” Control may also contribute to good health. A study of macaque monkeys showed that those monkeys with the least amount of control over their lives were unhealthier than the other monkeys. Lack of control leads to stress, which is harmful to all of us.

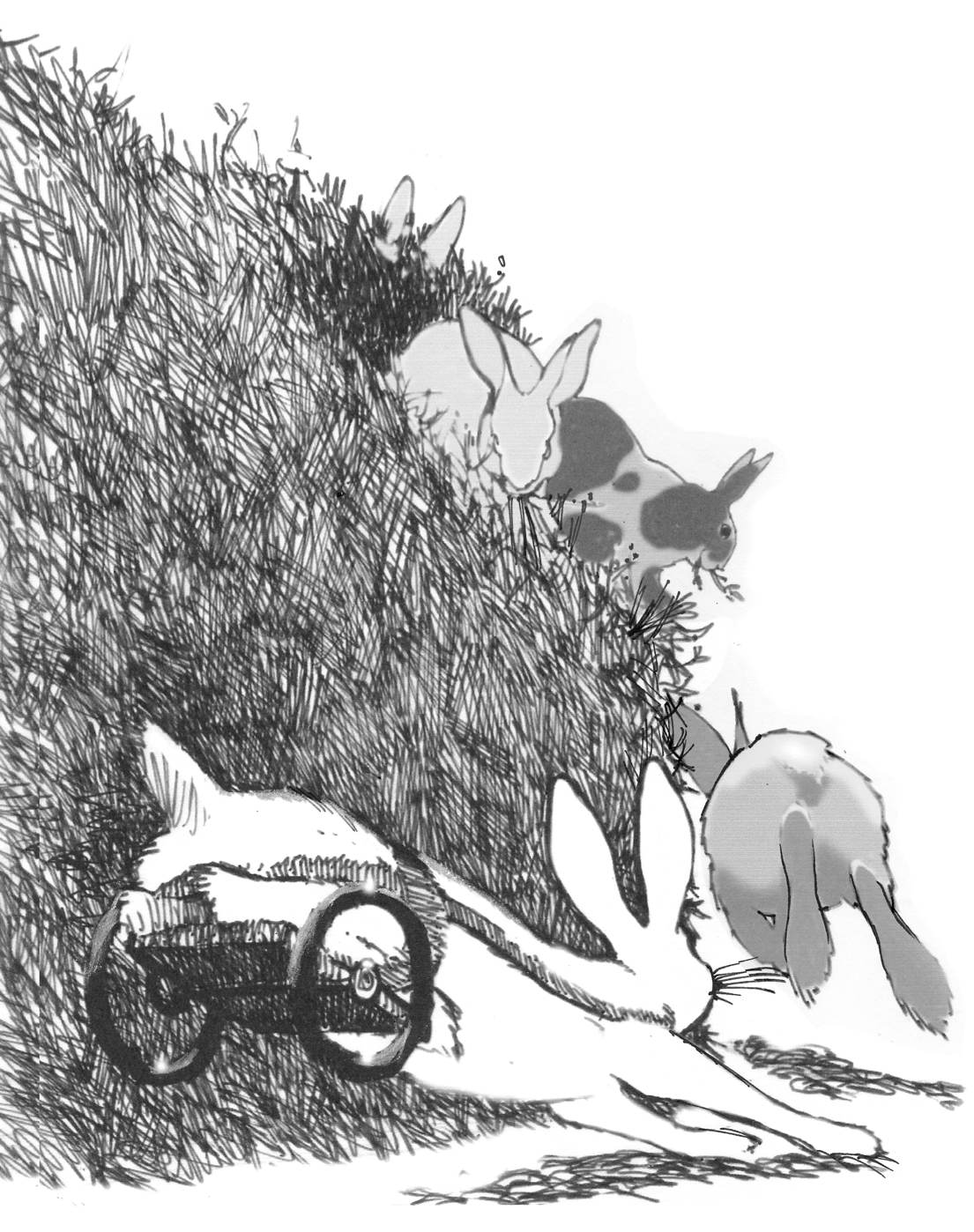

Right now, Audrey, a small white rabbit with a broken back, lives with me. She is feisty and proud and hates to be caged. Unfortunately, when I’m not with her, a cage shared with a partner is the safest place for her to be. But when I’m home, I try to let her out every day to roll around the house in her custom-made cart. She roams up and down the hallway, harassing the rabbits in the guestroom, teasing Igor in the living room. Because of her feistiness, she’s chewed through two different harnesses so far, so when she’s “between carts,” as I’m trying to get her harness fixed, she just scoots around on the floor. If she thinks I’m going to try to catch her to put her in her cage, like an able-bodied rabbit, she’ll scoot under the bed or dresser so I can’t.

Cultural Translation: SEEING RABBITS

Anthropologist Talal Asad once wrote about how the translation and interpretation of other cultures by Western anthropologists can be highly subjective and problematic due in part to the “inequality of languages.” The anthropologist is both the translator and the author of that which is being translated, because it is he or she who has final authority in determining the meaning of the behavior being studied. Cultural translation, thus, is inevitably enmeshed in conditions of power.

This same problem exists, arguably to a much greater extent, when trying to understand, and put into human words, the minds of nonhuman animals. How do we know what they want? For me, solutions to this problem exist in setting up conditions where human and nonhuman can coexist as equitably as possible. This not only begins to undermine the power differential separating the species, but also opens up the possibility of understanding other animals on their own terms.

Realistic Coexistence

The reality is, however, that it’s very difficult to achieve the kind of ideal coexistence I describe above unless one is extraordinarily tolerant. It becomes even harder when living with a human partner. Igor, for instance, is the small gray rabbit who dominates the living room. In seeking new forms of “interaction,” he has chewed a softball-sized hole in the wall, severed the bunny-proofed lamp cord, and, most recently, gnawed a small hole in our brand new couch. None of these assertions by Igor for freedom, independence, and the need to interact with his environment amused my husband.

We recently got a screen door for the door between the dining room and the courtyard. Immediately after its installation, Audrey rolled up in her cart to investigate—and promptly chewed a hole through it. Again, my husband was not amused.

In my house, as in yours, equitable coexistence is an ongoing process. It involves a lot of compromise, on the rabbits’ side and our own. But in the end, the attempt at allowing rabbits to live as rabbits is the ultimate goal.

©Copyright 1994-2026 Margo DeMello. All Rights Reserved. Republished with the permission of the author.This essay was first published in House Rabbit Journal Volume 5, Number 8.