Cardiac disease is a more frequent diagnosis as our companion rabbits live longer. The condition is sometimes present in conjunction with other diseases. Factors influencing the diagnosis and treatment of heart disease include age, genetics, other disease that might be present, and diet. Different areas of the heart may be affected, including the heart muscle, valves, or electrical conduction.

Small mammals generally have faster heart rates than larger-sized mammals, and rabbits are no exception. Dr. Stewart Colby – who treats many rabbits at his hospital, provides more detail:

A rabbit’s heart rate is much faster than that of a dog or cat, and a rabbit’s heart rate can vary due to a number of reasons. A rabbit at rest normally has a heart rate that ranges from 140 to 180 beats per minute.

Stress can cause the heart rate to increase, and the rate in a stressed rabbit can be quite high: well over 300 beats per minute – over five beats per second – which is impossible to accurately count except by specialized equipment.

Cardiac disease is not as easy to detect in rabbits as it is in cats and dogs, partly due to the fast heart rate. Dr. Noella Allan, a veterinary general practitioner who has a special interest in rabbits, shares her experience with heart disease in this population.

When I began performing physical examinations on house rabbits, I found it much harder to differentiate their heart sounds and rhythms because the hearts beat is so much faster than in cats and dogs (especially during office visits, which may be stressful). I’d pick up irregularities in the rhythm, abnormal sounds, and more muffled sounds, making it necessary to perform additional diagnostics.

In my practice, I’ve seen cardiomyopathy (heart muscle disease) and irregular heart rhythms. Cardiomyopathies may well have some genetic component, and giant breeds may be more susceptible. Abnormal heart rhythms can arise from a variety of problems, among them heart disease, systemic infections (which are suspected to interfere with heart conduction pathways), and electrolyte imbalance.

It should also be noted that some cardiac disease can result in pulmonary edema [excessive accumulation of fluid in the lungs] or ascites [fluid in the abdomen], both of which are associated with congestive heart failure.

Signs of Cardiac Disease

Signs of heart disease may not be detected until a rabbit is brought in for a routine evaluation. Dr. Susan Brown, who has been an exotic animal veterinarian for over thirty years, with a special interest in rabbits, offers the following information:

Often there is no previous history of a heart problem, or the disease might be in the very early stages. When cardiac problems occur at the same time as a more noticeable disease, the heart problem might get overlooked.

Often a cardiac problem shows obvious clinical signs when the rabbit is stressed by exercise, excitement, or anxiety, which cause the heart rate to increase. The following signs can indicate a potential heart problem in rabbits:

- Decrease in activity level (lethargic or only able to exercise for very brief periods)

- Weakness

- Reduced appetite

- Abdominal distension

- Weight loss or gain

- Distinctive resting position, with the front portion of the body elevated; the neck and nose may be pointed upward

- Increase in respiration rate, particularly deeper inhale than exhale. The nostrils may flare and stay open longer when the rabbit inhales than when he exhales. The abdomen behind the ribs may move prominently in and out during breathing.

Dr. Brown advises that caregivers should be aware that these signs are not specific only to cardiac disease but are shared by other disorders. Therefore, observation of any of the signs warrants a trip to the veterinarian.

Diagnosis of Heart Disease

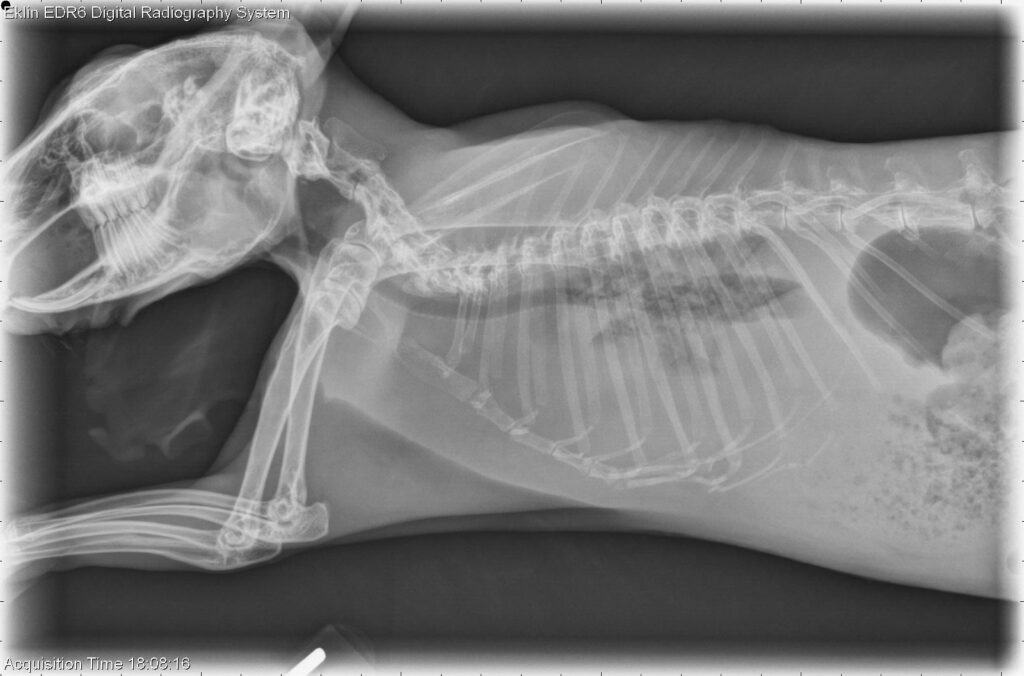

As already noted, a rabbit’s heart problem may not be evident to the caregiver. It may be during a routine evaluation, while the rabbit is sedated for some other procedure, or in a radiograph (X-ray) of the chest that the veterinarian notices an abnormal heart or lung sound or appearance. Sometimes it is a secondary condition that leads to the diagnosis of cardiac disease. Dr. Stewart Colby adds this from his experience:

When a rabbit presents with any respiratory issue or has abnormal lung or heart sounds, I usually begin diagnostics with radiographs. In many cases, heart issues are first noticed on radiographs taken for other reasons, such as gastrointestinal (GI) problems. Blood work, including for thyroid function, is also performed. Depending on the findings, electrocardiography (ECG) and ultrasound are the next step in diagnosing a particular issue, especially if medications are to be prescribed.

Once a cardiac issue has been identified, all underlying conditions should be ruled out to the extent possible and then managed or resolved in order to put less strain on the heart.

Because heart problems can be difficult to detect in rabbits, Dr. Allan may utilize the expertise of others:

I do the initial work-up and, depending on the need, obtain additional information from electrocardiography (ECG, read by a cardiologist to help analyze abnormal sounds or rhythms), echocardiograms (ultrasounds, performed by a radiologist or cardiologist to help evaluate structural and functional abnormalities), or thoracic (chest) radiographs. The latter test helps determine the size and shape of the heart, lung concerns, or the presence of a tumor of the thymus (thymoma) that may present with clinical signs similar to heart disease.

Since a rabbit’s heart rate is so high, it’s imperative that whoever is performing the diagnostics has the ‘normal’ baseline measurements for the particular rabbit or one of similar size.

Treatment and Prognosis for Recovery

Since most veterinarians are unfamiliar with treating cardiac disease in rabbits, consultations with those who have experience in addressing the disorder are recommended. Dr. Allan says this:

Treatment protocol is primarily based on medications used in other small animals, especially dogs and cats. ACE [angiotensin-converting enzyme] inhibitors allow the heart to work more easily by decreasing the resistance of the vessels into which the heart pumps the blood, while at the same time increasing somewhat the strength of the contractions. We’ve also used medication that alters heart rhythms and/or rates, such as one that slows down an abnormal heart rate to allow for a more normal sequential heart contraction and blood flow. Diuretics can also help when congestive heart failure symptoms, such as excess fluid in the lungs, become a problem.

Given that heart disease in rabbits is not well documented, prescribing the correct dosage of particular medications can sometimes be tricky. In addition, pharmaceuticals are constantly evolving. I work with a cardiologist who is extremely helpful in fine-tuning medications to minimize side effects.

Dr. Colby offers additional perspective:

As already mentioned, medications used on rabbits with heart disease are the ones used for other animal species, including humans. The primary effect of most of the medications is to lower blood pressure and put less strain on the heart. In rabbits this can become problematic because with lower blood pressure, GI problems start to become an issue, sometimes more so than the cardiac issues. That said, each rabbit is different and I would never rule out medications that affect the heart and blood pressure. But I also investigate the underlying problems, and in addition to any medical protocol I recommend managing weight and keeping excitement and stress to a minimum.

If a rabbit has heart disease he generally will not recover, but in many cases the clinical signs can be managed. One of my goals then is to try to limit further damage to the heart muscle itself.

It may be that other treatment measures are called for as well, since heart disease can be secondary to another condition. Dr. Colby offers this:

Some primary diseases that can cause secondary cardiovascular problems are kidney or liver failure as well as cancer that affects the lungs or areas around the heart, causing cardiac tamponade (an acute accumulation fluid in the sac that surrounds the heart).

Rabbits with heart disease can and do live good lives. But, as Dr. Colby points out, the long-term prognosis for a rabbit with cardiovascular disease is guarded only because there currently is no real cure for the disease. Therefore, tender loving care is needed, and this, along with mitigating or relieving the preexisting issues, often enables a rabbit to live a good life. When a rabbit with cardiac disease is not in respiratory distress, Dr. Colby does not recommend euthanasia.

Home Care of a Rabbit with Heart Disease

Home care for a rabbit with cardiac disease will vary, depending on the cause. As Dr. Colby noted, tender loving care and minimal stress are part of his recommended home-care regimen. Since stress can cause a sustained elevated heart rate, the need for a low-stress environment cannot be overemphasized.

Because a rabbit’s chest cavity is small (compared to the rest of the body), weight gain becomes an important factor in compromised health. Thus, Dr. Allan advises guardians to keep rabbits from becoming overweight, which severely taxes the heart. A good diet, plenty of exercise and social time, and a low-stress environment are critical to a rabbit’s health and well-being. (Reference diet and health-related articles posted on this website.)

In many cases, rabbits with early or less severe heart disease can live normal lives. They may not always be as active as their other furred buddies, but with mindful, loving care they can oftentimes enjoy life as fully as healthy bunnies do.

Additional Considerations

Caregivers may want to consider supplementing their rabbit’s care with alternative therapies, some of which are addressed in separate articles posted on this website. There are times when combining the expertise of both standard and alternative treatments offers the best supportive care.

When researching complementary treatments, be aware of training and qualification requirements and give careful consideration to the health, nature, and needs of your rabbit. Be clear and realistic about your expectations and goals for treatment, which should prioritize your rabbit’s comfort and quality of life.

Bibliography

My sincere thanks to the veterinarians named in this article for sharing their expertise during personal interviews and for their additional feedback. The following publications are pertinent to this article.

- BSAVA Manual of Rabbit Medicine and Surgery. Anna Meredith and Paul Flecknell (Eds.)

- Clinical Radiology of Exotic Companion Mammals. Vittorio Capello and Angela Lennox

- Color Atlas of Small Animal Anatomy: The Essentials. Thomas O. McCracken and Robert A. Kainer with David Carlson

- Exotic Pet Behavior: Birds, Reptiles, and Small Mammals. Teresa Bradley Bays, Teresa Lightfoot, and Jorg Mayer

- Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents: Clinical Medicine and Surgery. Katherine E. Quesenberry and James W. Carpenter

- The 5-Minute Veterinary Consult: Ferret and Rabbit. Barbara L. Oglesbee

- House Rabbit Handbook: How to Live with an Urban Rabbit. Marinell Harriman

- Notes on Rabbit Internal Medicine. Richard A. Saunders and Ron Rees Davies

- Rabbit and Rodent Dentistry Handbook. Vittorio Capello with Margherita Gracis

- Rabbit Medicine & Surgery. Emma Keeble and Anna Meredith

- Textbook of Rabbit Medicine. Frances Harcourt-Brown

Further Reading

- Thymomas in Rabbits

- WabbitWiki: Thymomas in Rabbits: Symptoms, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Experiences.

- Tumors In Rabbits by Marie Mead

- Pasteurella: Its Health Effects In Rabbits by Marie Mead

- Overweight And Underweight Rabbits by Marie Mead

©Copyright Marie Mead. All Rights Reserved. Republished with the permission of the author.

I wish to extend my sincere gratitude to Drs. Noella Allan, Susan Brown, and Stewart Colby for sharing their expertise in this article and additionally to Dr. Brown for her overall review of the article. Warm thanks also to Sandi Ackerman, Dr. Stephanie Crispin, Gary McConville, and Karen Witzke for their suggestions. – Marie Mead

Noella Allan, DVM, has been treating rabbits and other pocket pets since graduating from Michigan State University; she became more involved with their special needs when working as an emergency veterinarian. Dr. Allan practices at Noah’s Ark Animal Clinic in Kansas City, Missouri.

Susan Brown, DVM, is the founder and former owner of Midwest Bird and Exotic Animal Hospital (originally in Westchester, Illinois) and the current owner of Rosehaven Exotic Animal Veterinary Services and The Behavior Connection (North Aurora, Illinois). She is coauthor of Self-Assessment Color Review of Small Mammals and author of numerous lay and professional writings on rabbit medicine and care; she has also lectured extensively in the United States and Europe. She is involved in exotic animal care at rescue organizations and shelters. Utilizing the principles of behavior and training, she is teaching ways for people to live in harmony with their companion animals.

Stewart Colby, DVM, obtained his veterinary degree from the University of Georgia and is the founder and veterinarian at Windward Animal Hospital in Alpharetta, GA. He specializes in small animal medicine and surgery and has extensive experience with avian and exotic species. He works with the Georgia House Rabbit Society to help rehabilitate abused and abandoned animals, and he also assists in the care of exotic species at the Chestatee Wildlife Preserve and the North Georgia Zoo.