One of the most frequent questions I am [asked] is, “My rabbit’s nose and eyes are running. Did he catch a cold from me?” Fortunately, your bunny cannot contract a human cold, as the viruses that cause such misery in humans are not contagious to rabbits. (Note that rabbits can serve as vectors for such viruses. If you have a cold, be sure to wash your hands before you pet your bunny, lest you inadvertently share your “germs” with the next person who pets the bunny!)

As many people are all too aware, however, rabbits can suffer from sneezing, runny nose, and runny eyes. The particular cause of this in your bunny may require a bit of detective work on the part of your rabbit-experienced veterinarian, but the following information may help.

Upper Respiratory Infection (“Snuffles”)

Rabbits can suffer from infections of the upper respiratory tract (the sinuses and other parts of the tract that are not actually parts of the lungs), and this is usually manifested as runny nose, runny eyes and sneezing. Unlike a human cold, which is caused by a virus, rabbit upper respiratory infections are caused by bacteria. The condition is commonly called “snuffles.”

“Snuffles” is is a non-specific, “catch-all” term used to describe such symptoms without naming the specific cause.. Until fairly recently, many veterinarians believed that “snuffles” was almost always caused by the bacterial pathogen Pasteurella multocida, commonly found in rabbits (though often without causing any problematic symptoms at all). More recent information suggests that many different species of bacteria can cause “snuffles.” Some of the bacteria most commonly cultured from rabbit nasal discharge include Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bordetella bronchiseptica, and Staphylococcus aureus, though there are many others.

Because bacterial species (and their different strains) have characteristic sensitivity and resistance to various antibiotics, it is worth your investment to allow your veterinarian to positively identify the pathogen (i.e., disease-causing agent) your bunny has. The best way is via a CULTURE AND SENSITIVITY test. This laboratory test is the only way to determine (1) the species of bacteria causing the infection and (2) which rabbit-safe antibiotics will be most effective at killing them.

If your rabbit is sneezing and/or shows signs of nasal and/or ocular discharge, especially if such discharge is whitish and thickened, she needs to be seen by a veterinarian and have a sample of nasal discharge taken and sent to a laboratory for culture and sensitivity testing. Once your vet receives the results of the C & S test, s/he will be better able to prescribe the particular antibiotic (or combination of antibiotics) that should be safest and most effective for your rabbit’s infection.

Antibiotic therapy may need to be continued for several weeks, and it should always be continued for several days after symptoms have disappeared to ensure that as much of the bacterial population as possible has been killed. Follow your veterinarian’s instructions carefully, and be sure to complete the full course of antibiotics, even if the symptoms go away before the medicine is gone. The reason for this? Even the most effective antibiotics might not kill some of the more resistant bacteria right away. Removing the drug too soon will leave only these particularly hardy individuals to be the progenitors of the new population of bacteria in your rabbit’s sinuses, and these will be genetically better able to resist the antibiotics you have been using (i.e., the population has evolved resistance to the antibiotics). Don’t stop the antibiotics early, and don’t put off treatment! A seemingly simple condition such as sneezing could develop into a potentially life-threatening problem, such as pneumonia or a systemic infection.

Lower Respiratory Infection

A rabbit with pneumonia may show symptoms such as loud, raspy breathing, and may point his nose high in the air and stretch his neck in an attempt to get more oxygen. A rabbit in this condition is critically ill, and in need of oxygen therapy at your veterinarian’s clinic. Experienced rabbit veterinarians will often nebulize such a bunny with oxygen as well as products to open the airways (e.g. aminophylline) and to loosen the mucus and infective material in the lungs (e.g., acetylcysteine solution, brand name “MucoMyst”). In some cases, the veterinarian will add appropriate antibiotics to the nebulization mix, depending on what a culture and sensitivity test indicates.

Foreign Bodies

In some instances, a foreign object (such as a strand of hay, or a bit of food pellet) lodged in the nasal passage has been found to be the cause of runny nose and apparent chronic nasal infection. Sometimes such a foreign body is not visible without the aid of an endoscopic examination by your veterinarian. Once the item has been located, it is usually necessary to anesthetize the rabbit to allow removal of the object without danger.

In other cases, nasal polyps or other growths are found to be at the root of chronic upper respiratory symptoms. But surprisingly, one of the most common culprits causing chronic “snuffles” is undiagnosed dental problems.

Dental Disorders and Chronic Runny Eyes/Nose

Many people are surprised at how common dental problems are in rabbits, and even more puzzled to learn that such problems can cause symptoms such as runny eyes and nose. This is more often seen in older rabbits, as these have had time to develop molar spurs, or molar root problems that can cause inflammation or even develop into infections that spread to the sinuses.

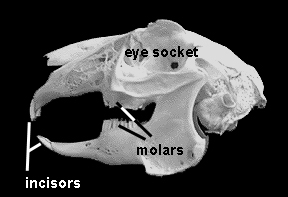

In some older rabbits, gradual onset of metabolic bone disease results in loss of bone density (osteoporosis), especially in the already light bones of the skull. When this happens, the molar and/or incisor roots can very gradually be pushed into the thinning bone as the rabbit chews.

Because rabbit teeth grow continually, the visible portion of the teeth may appear entirely normal. It is only upon radiography that the root problem becomes visible as an intrusion of the tooth roots into the skull bones. This sometimes been called “root overgrowth,” though the term is a bit of a misnomer. The roots are not actually “growing” into the skull, but are being pushed there.

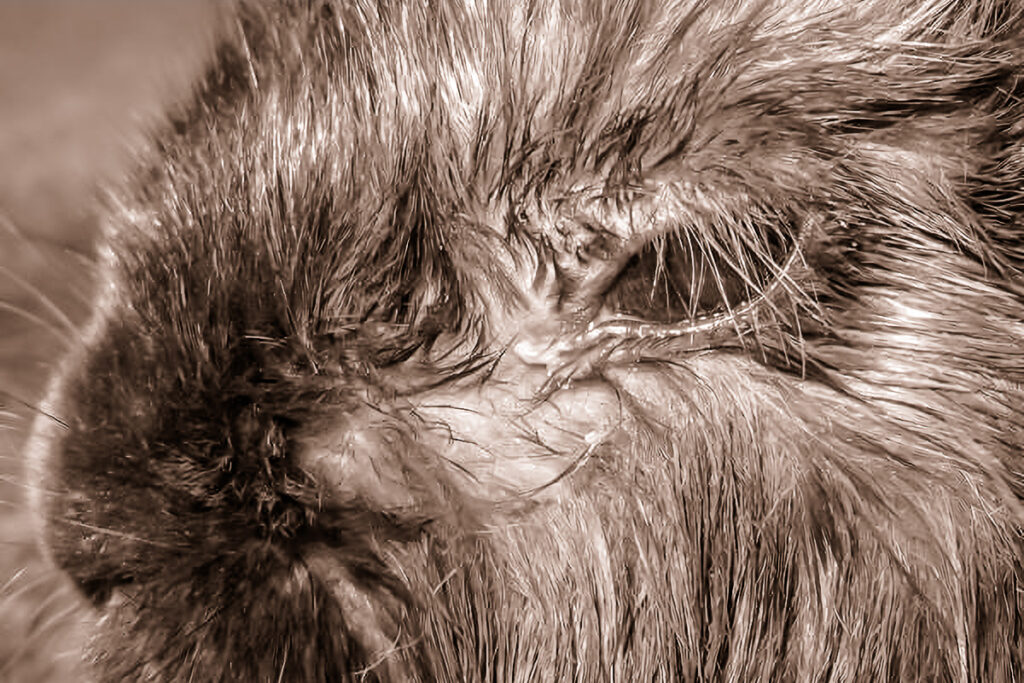

A rabbit’s molars are located almost directly under the eyes. Hence, molar root intrusion into the skull bones can cause occlusion (blockage) of the tear ducts, which run through the skull bones, close to the roof of the mouth, just above the tooth roots. A blocked tear duct will cause tearing and runny eyes, since the tears cannot flow through the ducts and into the back of the mouth, where the duct normally empties. A narrowed duct is more susceptible to becoming plugged with mucus or bacteria. If the duct is not completely occluded, it is often possible for your vet to flush the ducts and help restore normal flow. Whatever discharge comes out the nose from the flush can be A rabbit’s molars are located almost directly under the eye socket. When molar problems (spurs, root intrusion, abscess) develop, symptoms such as runny eyes can be a clue that something’s amiss. collected and sent to a lab for culture and sensitivity testing.

Severe molar root intrusion can also be the cause of retrobulbar abscesses (i.e., abscesses located behind the eye, inside the skull). In some cases, the root has been known to puncture through the bone of the eye socket and into the eyeball itself, causing an intraocular (i.e., inside the eyeball) infection. Such severe problems may require the expertise of a licenses veterinary ophthalmologist, and your own vet may be able to refer you to one in your area, if necessary.

Even incisor (front tooth) roots can be pushed backwards into the skull and occlude the tear ducts. Again, this is usually visible only with radiography. Although your vet may suggest that incisor or molar removal may solve the teary eye problem, there are no guarantees. If the chronic trauma to the area already has caused enough scarring in the bone, even tooth removal may not open a blocked duct. You and your vet should confer to decide whether complete tooth removal to attempt to restore tear duct function is worth the risk.

Alleviating the Symptoms of Runny Eyes and Runny Nose

Runny eyes that cannot be permanently repaired via tear duct flush may cause skin burns and irritation where the caustic tears collect on the skin. It is usually helpful to apply warm washcloth compresses to the affected areas daily, to help soften the dried tears, and then gently rub them away. A fine-toothed, small flea comb may be useful in helping remove softened crusts from the fur.

One excellent way to help a bunny with chronic runny eyes is to allow him/her to choose a spayed/neutered mate from among those at your local rabbit rescuer’s foster home. Bonded bunnies spend a good deal of time grooming each other’s faces, and we know of some bonded bunnies who once had very irritated skin from constant tearing who became completely symptom-free once they had mates to groom away those tears.

A very clogged nose is definitely a problem, as rabbits are obligate nasal breathers. You can help clear your bunny’s nose temporarily by gently suctioning with a pediatric ear syringe. Ask your vet about using a mild, pediatric antihistamine such as Benadryl to help shrink swollen nasal membranes. Together with a tear duct flush, which also helps flush the nasal passages, these treatments can be very effective at clearing the bunny’s breathing route.

Whatever the cause of your bunny’s problem, the sooner you allow your vet to perform the right tests and prescribe the proper treatment, the better your bunny will be able to breathe easily and be on the road to better health.

©Copyright Dana Krempels. All Rights Reserved. Republished with the permission of the author.