Editor’s Note: Rabbits often enchant us with their blend of curiosity, charm, and a touch of mischief, but truly understanding what makes them tick can be a lifelong pursuit. Few have delved deeper into the minds and behaviors of these delightful creatures than Tamsin Stone, whose passion for rabbits began in childhood and grew into a profound exploration of rabbit behavior and welfare.

At the heart of Tamsin’s journey was Scamp, a European wild rabbit rescued as a newborn. Hand-reared and deeply bonded with Tamsin, Scamp defied expectations about the limits between wild and domestic rabbits. His affectionate antics and extraordinary athleticism not only captivated Tamsin but inspired her to create an invaluable resource for rabbit caregivers, “Understanding Your Rabbit’s Habits“.

Tamsin’s commitment to rabbit advocacy extends far beyond her writings. She founded Rabbit Rehome, a pioneering rabbit adoption network in the UK, and actively maintains The Rabbit House, a comprehensive online platform that educates rabbit guardians worldwide. In our conversation, Tamsin shares illuminating insights into rabbit behavior, addresses common misconceptions, and emphasizes the importance of continuous learning to enrich the lives of our furry companions.

I’d love to hear more about Scamp—what was it like to have a wild rabbit in your home? Did he interact with any of your domestic rabbits?

Scamp came to me via my vet, after a construction worker saved a nest of babies that had been scooped up in the bucket of a digger. They were a few days old, with only the first hint of fur and their eyes still tight shut. Unfortunately, hand rearing such young rabbits successfully is tricky and Scamp was the only one that made it past the first few weeks.

As Scamp grew up, the differences and similarities between him and a domestic rabbit were really fascinating. Here in the UK wild rabbits are the same species as domestic rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus), so it really was the classic nature v. nurture. Scamp turned out as tame as any house rabbit. He would flop over next to me (sometimes rolling all the way over in his enthusiasm) then nap whilst I delivered nose rubs.

He begged for food, and would hop up on the to sofa to demand treats. He was litter trained (he had been neutered). He had no problem with being handled, picked up and carried, or even having his nails trimmed. He very much enjoyed being groomed, and would frequently return the favour by licking my hands or clothes. One of his favourite activities was to play a sort of chasing binky game where he would circle the room at high speed binking, whilst I followed (much slower) occasionally catching up for a few nose rubs. The game ended when he hopped up and flopped across my feet.

It really highlighted the impact of human-rabbit socialisation to me. Here was this wild rabbit, who should have been incredibly wary but had such a close and trusting relationship with humans. To me it really highlights how much of the way individual rabbits interact with humans is down to the experiences you share – the time you spend with your rabbit whether you are cleaning up poop, feeding them or just hanging out in their space is all building trust and confidence with people. Those that have worked with rescue rabbits will know this – a shy scared rabbit can learn to trust with patience and building that bond is incredibly rewarding.

Of course, living with a wild rabbit isn’t all easy sailing; Scamp was an education in bunny proofing. He was smart, physically skilled and determined so the bunny proofing was a constant work in progress and enrichment was an absolute necessity. The athleticism of a wild rabbit is truly amazing. Scamp weighed a touch under 1kg (2.2lbs) – which is about the size of a Netherland Dwarf. However, he was not built like a domestic rabbit; he was all leg and muscle and he made domestic rabbits, even the more naturally shaped ones, look short, stubby and unfit.

His binkys were epic and he could easily jump from floor to the kitchen worktop or over a 4’ barrier without a run up – he almost seemed to float it was so smooth and effortless. And he chewed, a lot! I would go out daily foraging for him, providing fresh grass, a range of wild plants and fresh sticks and branches for gnawing on – he loved stripping the bark from apple branches.

I did try briefly introducing him with a domestic rabbit as an adult, but is was obvious fairly quickly the two weren’t a good match – there wasn’t aggression but Scamps high speed enthusiasm was quite intimidating and he wasn’t particularly interested in interacting – I’m not sure he grasped he was a rabbit. In fairness though I didn’t pursue it so it may have been the right match and more time would have had a different outcome – it’s certainly something that I’d focus on more if I was in the same situation today.

What led you to write the first edition of Understanding Your Rabbit’s Habits? Tell us more about the beautiful drawings!

When I got Scamp, I did what I’d advise anyone caring for an animal to do – a lot of research. Although I’d had domestic rabbits for a long time, I wanted to learn more about wild rabbits. I poured through journal articles, books, and video footage and even spent time watching the local wild rabbits. Some of the research is difficult to read as the perspectives aren’t necessarily the same as those of us caring for rabbits. Still, it was very educational – the more I learned, the more I understood Scamp, but it also helped me to understand the roots of behaviours I had observed in domestic rabbits.

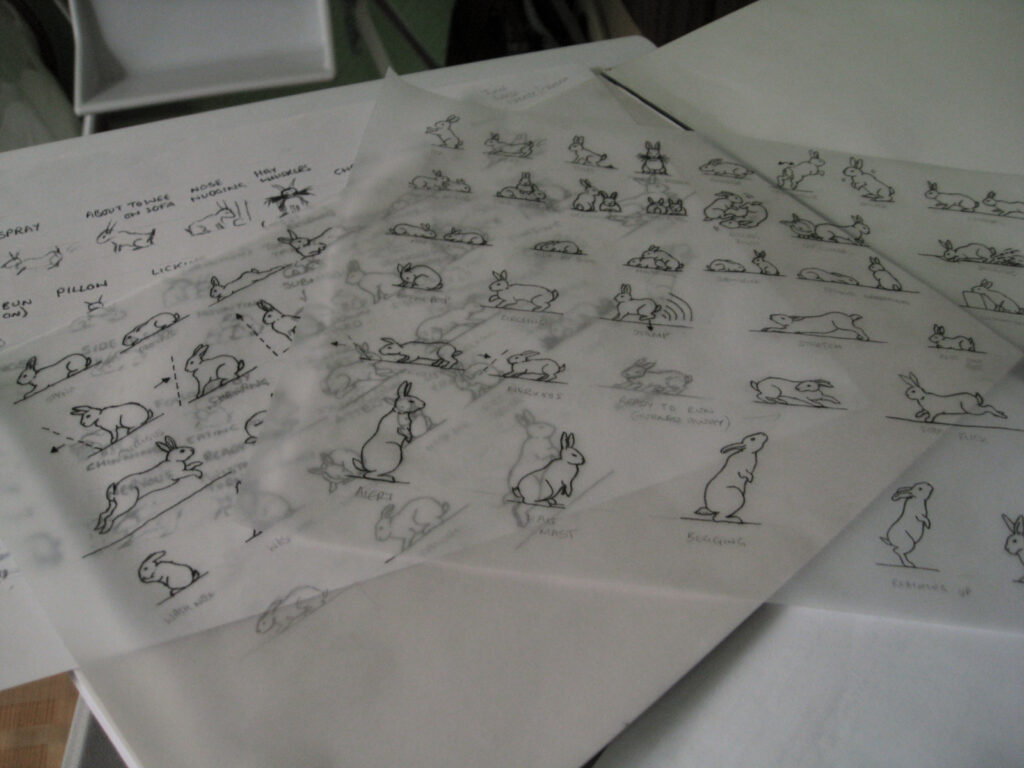

The illustrations actually came first—the book began life with pages of little rabbits as I tried to capture all of the different behaviours that I had seen in Scamp and my domestic rabbits. What I’d learnt about wild rabbits was a real eye-opener for me. That knowledge changed how I cared for my rabbits and what I prioritised, and I wanted to share that understanding with others.

Take providing a hideaway, for example; I can understand how having a shelter for a house rabbit seems a bit pointless: if you do have one, your rabbit may not use it much, and open-top beds are very popular. Whereas if you understand the way a rabbit is wired you realise how much benefit that small enclosed place of safety is to a rabbit’s confidence, even if they don’t use it often, and how essential it is to those unpredictable moments when you rabbit might be scared. Everything about a rabbit, from their excellent senses to their big back feet, is built for reacting to danger with a sudden short burst of speed to get them to a place of safety.

As much as we try to keep our rabbit’s safe, there are many potentially scary things that we know won’t hurt them but they don’t – fireworks, an accidently dropped pan, a fire alarm. Then the instincts from their wild ancestors kick in – I’ve seen a domestic rabbit in absolute blind panic fling themself into walls because their instincts say they need to escape and they don’t have that safe enclosed hideaway to run to. It doesn’t need to be big, but an enclosed box with an entrance (two if you can), even if it’s just cardboard, is essential for every rabbit!

What inspired you to create this updated second edition? Are there new insights or research you were excited to include?

In the second edition of Understanding Your Rabbit’s Habbits, I wanted to expand on the social aspects of rabbit behaviour. I think there is growing recognition of the importance of companionship, and that’s reflected in the number of rabbits living in pairs, but it also means more people trying to navigate those relationships. Rabbits can be confusing: on one hand, they are incredibly social, but bring them home a friend, and odds are you’ll have a fight on your hands. There is a lot of practical advice on bonding rabbits, but I wanted to go back a step and look at how rabbits form groups and what we can learn from that.

Once you look at rabbit social structure and living arrangements, you can see why things go wrong and how to support your rabbits through introductions. There is also a lot of value in understanding why something works or doesn’t, rather than just following instructions then you can recognise the difference between good advice and bad and tailor it to your rabbits and situation.

Some of the relationship-forming behaviour is also important to our relationships with rabbits. When first meeting, rabbits often spend a lot of time sharing a space without directly interacting, and we don’t always recognise the importance of this. Taking a step back and not going straight in for cuddles is much more respectful of how rabbits like to meet new friends.

By the time I was done, though, almost every section of the book had more detail and illustrations!

How did The Rabbit House begin, and what are its core missions in rescue and education?

My website—The Rabbit House—began almost twenty years ago. I was running a large rabbit forum and answering many questions from rabbit owners seeking help. I’ve always felt that when trying to share education, it’s important to not just give instructions but explain the reasons behind the advice. I want people to have the information to make informed decisions about how to best provide for their individual rabbits’ needs.

I enjoy the challenge of delving into the details of hot topics and presenting information in a way that is easy to understand – you’ll find a lot of diagrams, infographics, and the odd little interactive widget on the website. One of the most popular pages on my website is the giant table comparing the ingredients of different rabbit food brands. I initially added it to support education campaigns that were running in the UK around swapping from muesli mixes to complete pellet foods. At the same time we were telling people to not choose muesli, I wanted to provide information to help people unpick the choices available and work out what was right for their rabbit.

What unique challenges affect rabbit advocacy in the UK? What common issues do you see shared with the USA?

I love that the internet means we can share knowledge from so many different places around the world. Historically, it has been very normal to keep a rabbit outside in a small wood hutch in the UK. We don’t have quite such the extremes in climate or variety of predators as the USA but it still created a lot of welfare issues. A big one being it put rabbits out of sight, and unfortunately often out of mind and even when they had basic needs met they didn’t have the quality of life that a rabbit should have. Education around the size of accommodation, the need for space to exercise and companionship of other rabbits has made a lot of progress. There is always work to do, but I think it’s also important to recognise that progress has been made. When I look at the difference in what is sold as a basic setup in a pet shop today verses ten years ago the change is remarkable.

I think the USA has been a big influence on the UK in terms of house rabbits—people see the relationship you can have with rabbits sharing a living space, and that’s very appealing, which in turn has been good for welfare.

I think we struggle with many of the same challenges—rabbits sold in pet shops as impulse purchases, people who care for their rabbit but aren’t aware of rabbits’ needs, and, of course, rescues that are overwhelmed with the number of unwanted rabbits. Myxomatosis and RVHD have been big issues in the UK—I know that, unfortunately, the USA has begun to experience that, too.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about rabbit behavior that you frequently encounter?

There are many misconceptions around how active it’s normal for rabbits to be. We often make life to easy for them so they end up spending too much time sitting around with nothing to do. Beautifully arranged living spaces with pre-prepared sleeping areas and meals that arrive in the same spot like clockwork seems like a good thing, but it takes away all the usual activities a rabbit would fill their day with. That, in turn, often leads to conflicts when rabbits end up bored or frustrated.

I think the biggest misconception around rabbit behaviour is the idea that rabbits are deliberately stubborn, destructive or naughty. All of the behaviours that we see as problematic are really just rabbits trying to navigate a human world that’s very different to the one they evolved to inhabit. For example, it’s perfectly natural behaviour for rabbits to dig at the ground; I imagine they are just as frustrated at the difficultly digging through carpet as you are with the hole they leave in your new rug.

Appreciating what normal behaviour for rabbits actually is can go a long way to addressing misconceptions and knowing how to cater to your rabbit’s needs. That’s what hope reading my book gives people that understanding of what rabbit’s want in life – what makes them happy and fulfilled.

Can you share a memorable success story in which your guidance changed someone’s understanding of their rabbit?

I remember one lady who was having trouble with a pair of rabbits – she loved them to bits and it was getting to the point where she was worried she would need to separate them and rehome one because they were getting so aggressive with each other. She’d done all the right things, they were checked by a vet, they were already neutered and they had a lovely spacious setup. We talked back and forward about it and what was happening around the time the aggression happened and it was always around meal times. She’d go into the room at mealtime and that would kick things off – they would circle each other, circle her feet, grunt, growl and it just kept escalating until they were having scraps with each other.

The solution – get rid of the mealtime. Mealtimes are one of those human-world inventions and not something natural to rabbits who spend all day grazing. The arrival of really high value calorie packed food (rabbit pellets) was exciting to them and there is quite a lot of overlap between excited and aggressive in rabbit body language so it escalated the situation in ways they probably didn’t intend. The more they got overexcited, the quicker she rushed through getting the food in the bowl, and it turned into a vicious cycle, with everyone involved stressed out.

By changing the ‘meal time’ routine, feeding more hay and fresh foods and broken up during the day rather than at the original meal time the trigger for the excitement and resulting aggression was gone. Pellets were reduced and scatter fed or mixed with piles of hay so there was no bowl to get possessive over. It’s one of those situations where figuring out what is going on in your rabbit’s brain and looking at the situation from a rabbit perspective is really helpful to working out the solution to the problem.

8. Many people underestimate how much mental stimulation rabbits need. What are your favorite ways to keep them engaged and happy?

I completely agree. I like to think about the things that would naturally fill a rabbit’s day and a big one is feeding – a wild rabbit would spend about half of the time they are awake eating. Something really simple like splitting your rabbits’ hay into several portions and placing it in different locations has a lot of benefits. Multiple feeding areas gives your rabbit choice, they can make decisions about where they want to feed and that’s really good mental stimulation – you can expand on that by using different style feeders or different heights e.g. on the floor or at nose level. You might find you learn something new about your rabbit’s preferences. As a bonus encouraging your rabbit to move around grazing in different places is also great for the digestive system.

I love natural sources of enrichment because they are low cost, give lots of opportunity for natural behaviours and are often really enjoyed by rabbits. My absolute favourite is big branches of rabbit safe foliage – apple tree, blackberry/bramble, raspberry canes, willow etc. It creates a temporary visual barrier – you can go around, under, over or through it so stimulates lots of investigative behaviours. It can be picked up, rearranged, or chewed if it gets in your way. Plus it’s another opportunity for grazing. If you’re worried about too many leaves your rabbit isn’t used to, pull off any extras and dry them for later feeding.

What advice would you give someone wanting to become more involved in rabbit advocacy?

I know sometimes it can seem a little daunting, like you don’t know everything so couldn’t have anything valid to contribute or the problem is so big you don’t know where to start, but it’s the little things that make a difference. When you show off photos of your rabbit enjoying toys to a co-worker and plant the idea of that’s how rabbits should live you are advocating. When you spot something you don’t think is right in your local pet shop and you say (or email) and tell them rather than walking away. When you take a moment to share your local rescues post or collect some educational materials to drop in your local library. Start with something that feels manageable to you and build on it.

Paige: If you could share one key message with every rabbit caregiver, what would it be?

To keep learning. Our knowledge of rabbit care and needs is something that’s still changing and growing. It means that sometimes what was best practice a year or two ago isn’t any more. Read as much as you can and take the opportunity to chat with your vet, rescues and other rabbit owners anytime you get it. Share what you know but be ready to listen to others, and be brave enough to admit when you’ve got things wrong and need to make a change.